Elias Jabbour argues that Western scholars turn Marx upside down in analysis of China, failing to see how it is developing a new socio-economic formation, an “embryonic socialism”, that cannot be simplistically reduced to the relations of production.

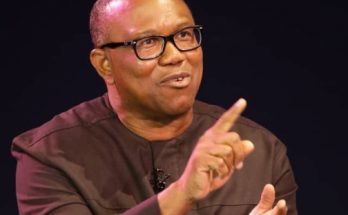

By Khalil Jabbour (Opinion piece published on Geopolitical Economy Report)

Elias Jabbour is associate professor of theory and policy of economic planning at Rio de Janeiro State University’s School of Economics, and co-author of the book “Socialist Economic Development in the 21st Century: A Century after the Bolshevik Revolution” (Routledge, 2022).

What determines the nature of an economic-social formation? Is it power over the fundamental means of production, or the relations of production?

Phrased differently, the question is even simpler: What comes first, the “economy”, or politics?

It seems evident that politics is paramount, and the nature of an economic-social formation must therefore be based on who actually exercises power, and which historical form of property is the qualitatively dominant one.

China provides a clear example of this. Although China’s private sector employs more people and is much larger than the country’s public sector, private companies are not responsible for generating chaining effects on the rest of the economy. Moreover, cycles of accumulation are not generated within China’s private companies. It is the public sector alone that concentrates this power.

This fact calls into question the claims of economists like Branko Milanović, who in his best-selling book “Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World”, argues that capitalism has inevitably taken hold in China, based on the purely quantitative aspect of its property relations.

But what is truly the nature of power in China? Is it the same as that of South Korea, Germany, or the United States? Or is it a new type of “socializing strategy”?

Some heterodox economists try to answer this question by pointing out that, in China, there are countless state enterprises, and that the government engages is economic planning. But this approach is mistaken.

These heterodox economists end up trapped in the idea ex ante, believing that China merely creatively applies theories that were already elaborated elsewhere, that it copies Japan, South Korea, and the “state industrial” model.

Western academics often analyze China’s state, market, and institutions, applying so-called “variants of capitalism”, but in doing so, they separate theory and history, and subject and object – and thus fail to overcome Kant and arrive at Hegel.

We argue that China has developed a unique dynamic of accumulation, a novel socio-economic formation, which we call the “New Projectment Economy“.

The fundamental mistake of many Western academics, even Marxists, is to turn Marx’s analysis upside down and propose that the relations of production determine the nature of an economic-social formation.

Following this logic, it would be possible to implement socialism immediately after slavery.

But the deepening of the social division of labor has nothing to do with the emergence and development of capitalism.

If it were this simple, everything would be resolved with a checklist: If there is surplus value, a labor market, and “exploitation”, the system is capitalism.

Those who work with this approach are in direct opposition to history as a way of organizing thought. They consequently do not perceive the continuities and discontinuities of history.

This view denies Hegel and Marx, for whom the concrete is the synthesis of multiple determinations – and, we add, “combinations” (“a” + “b” + “c”), in favor of the principle of Kantian identity: “a” is different from “b”.

But this Western, academic strain of “Marxism”, far from being able to find synthesis, looks for the manifestation in the real movement of something that is already finished in their own heads.

This is a petty-bourgeois way of thinking.

In reality, the exercise of political power requires much more than moral judgments.

China is a society in transition, from the countryside to the city, in which multiple contradictions manifest themselves simultaneously: the circulation of goods, social and territorial inequality, currency in its commodity form, a market, a private sector.

In our book “Socialist Economic Development in the 21st Century: A Century after the Bolshevik Revolution” (Routledge, 2022), Alberto Gabriele and I argue that the Chinese experience must be observed as a new socio-economic formation, from the bosom of which emerges a still embryonic historical form, one that we call socialism.

This “embryonic socialism”, like everything else in life, operates under historical and geopolitical conditions that were not chosen by the Communist Party of China.

We elaborate the concept of a “metamode of production”, to identify the broad restrictions imposed on socialism in peripheral realities.

This explains why China’s industrial sector and economic planning are market-oriented, and attentive to the limits imposed by the law of value.

We must always remember that Adam Smith perceived the deepening of the social division of labor as a characteristic of capitalism. Marx perceived in socialism the “overcoming of the social division of labor”.

The problem is that history writes straight, but in crooked lines.

Socialism is the only way to organize a society from scratch, in societies that were completely destroyed.

A country like China, in 1949, did not even have a social division of labor, much less accumulated productive forces capable of supporting new production relations.

The historical experience of the Chinese people still has a long way to go, especially given the technological strangulation imposed by the United States.

But this is a surmountable obstacle, one that must be seen as the “main aspect of the main contradiction”, given the fact that imperialism imposes a wall on the technological development of socialism.

This is class struggle in its supreme manifestation. And the concept manifests itself in movement, not in human will.